Lent is a time of fasting. In former times, in order to prepare themselves to live the great mystery of the death and resurrection of Christ, Christians not only fasted from food but also practiced an auditory and visual fast.

Auditory privation took the form of suppressing of the use of the organ and musical instruments, but also in many diocesan uses, suppressing the ringing of bells. Visual privation with the veils that were placed over the Cross and the statues or even the prohibition of placing flowers upon the altar. Visual privation also included closing off the sanctuary with a great veil, the velum quadrigesimale.

And so in Paris, until around the year 1870, such a veil was hung from the first Sunday of Lent until Spy Wednesday. This great veil, made of violet or ash-coloured linen, completely closed off the sanctuary and masked the view of the High Altar. It was dropped on the pavement of the sanctuary during the course of Spy Wednesday Mass during the chanting of the Passion according to St. Luke, precisely when the chronista reached the chanting of this verse: “et obscuratus est sol: et velum templi scissum est medium.” (Luke 23:45).

This dramatic visual action gave life to the words of the Gospel of the Passion that the faithful heard and reinforced its meaning in their hearts.

This great veil—called the velum quadrigesimale or velum templi—was not, however, particular to Paris, since it is found in all the lands of the ancient Carolingian world. Its usage is attested by many councils and medieval statutes and actually goes all the way back to Christian antiquity. Growing more and more ornate toward the end of the Middle Ages, especially in Germany, the Lenten veil, which had survived the Lutheran reform, is currently witnessing a renewed interest.

The Lenten Veil in the Ancient Use of Paris

Below are several paragraphs concerning the decoration of churches during Lent, taken from the Caeremoniale Parisiense published in 1662 by Cardinal de Retz, and edited by Martin Sonnet, priest and beneficiary of the Church of Paris, a reference work for understanding the old Parisian rite. This passage describes the set-up of the decoration of churches proper to the time Lent, carried out before First Vespers of the First Sunday of Lent. Regarding the great Lenten veil, the parisian Ceremonial stipulates not only when it must be placed in the sanctuary, but also at what precise moments it must be opened or closed.

*****

From the Sundays and ferias of Lent until Palm Sunday.

And when Jesus had fasted forty days and forty nights, afterwards he was hungry (Matthew 4:2).1. The first Sunday of Lent is a semi-double of the first class. Semi-double with respect to the office; first class, with respect to its privilege.

2. The Saturday before Vespers, the Master of Ceremonies ensures that the churchwarden or the sacristan and his assistants entirely cover up all crosses, reliquaries or relics of the saints, and images of the church, even the Processional Cross, in a dignified manner with a violet or ash-coloured veils made from camlet or damask silk, or from a silky fabric. He likewise ensures that the high altar and the other altars of the church be covered with frontals of the same colour.

3. And before the high altar, between the choir and the sanctuary, from one side to the other, a great oblong and wide veil is hung, or a large curtain made of violet or ash-coloured camlet, which can be drawn back or folded or let down when needful, or even spread out or closed or drawn, until Wednesday of Holy Week.

4. Now, this great veil is spread out for all ferial hours only, and for the entire day and night, and it is never spread out during mass, nor during the Sunday office from First Vespers until Second Vespers and for the entire day and night, nor indeed on the offices of double and semi-double feasts, nor by day nor by night.

5. Additionally, all draperies and all the carpets of the steps or the predella of the high altar and the other altars, are taken down throughout the Church: in sum, until Easter, the entire church is without ornament.

*****

Observe how the same Ceremonial describes the lifting of the great Lenten veil a little later, when it speaks about Spy Wednesday:*****

1. The deacon sings the Passion according to St Luke, which the celebrant meanwhile reads on the Gospel side, as is noted in the preceding Tuesday. Now, after he arrives at the eagle which is in the middle of the choir, the Master of Ceremonies extends the great veil between the sanctuary and the altar, in the usual manner. It is elevated in each part of the choir, and held by two clerics, until these words of the Passion: "And the veil of the temple was rent in the midst". And when the deacon pronounced those words, at the command of the Master of Ceremonies, the two aforementioned clerics immediately let go, so the veil may suddenly fall entirely on the floor of the choir, and it is afterwards taken away by the sacristan.******

It is very interesting to note that the great Lenten veil remains opened all Sunday, from First Vespers to Second: the Day of the Lord, Dies Domini, has always been the feast of the Resurrection, even in Lent. Fasting is forbidden on this day.

The Cæremoniale Parisiense of Cardinal de Noailles, published in 1703, moreover, quite reasonably postpones the installation of the veil until after Compline of the First Sunday of Lent and before the Night Office of Monday: since the veil remained open on all Sundays, its installation before First Vespers of the First Sunday of Lent—however it perfectly logically fit with the entry into Lent—was not absolutely necessary. According to this Ceremonial, the other veils on the images and crosses are nevertheless always installed before First Vespers of the First Sunday of Lent. As we shall see, the practice of placing the Lenten veil after Compline of the First Sunday is already found in most medieval monastic customaries from the 10th century, and perhaps this is a souvenir from ancient times—before St. Gregory the Great!—when the fast did not commence until Monday.

The Lenten Veil in the Rest of Europe

Before the Renaissance and the printing of the first diocesan ceremonials, it is not always easy to discover the development of various liturgical rites in exact detail: the rubrics in the old Medieval Missals are fragmentary or even non-existent. We may still glean several useful details in the acts of provincial councils, and especially in the Customaries of the Abbeys, which regulated the details of conventual life in each of the great monastic centers with great precision.

And so we find the great Lenten veil mentioned by a series of medieval Anglo-Norman councils as being part of the supplies that every church was obliged to possess: these are the councils of Exeter (1217), Canterbury (1220), Winchester (1240), Evreux (1240), and Oxford (1287).

Prior to these councils, a number of customaries, constitutions, and statutes of medieval abbeys witness to the custom of closing off the sanctuary with a veil during Lent.

The most ancient mention is found in the Consuetudines Farfenses, the Constitutions of the Abbey of Farfa, near Rome, produced around the year 1010 (ch. XLII), which notes for the evening of the First Sunday of Lent:

Nam denique secraetarius cortinam exacta vespera in fune ordinet et completorio consummato in circulos extendant.

And finally, after Vespers have finished, the sacristan shall set up a curtain over a cord and, at the end of Compline, they shall spread it out.

St. Lanfranc († 1089), abbot of Saint-Étienne in Caen and then archbishop of Canterbury in 1070, speaks in his statutes about the Lenten veil, which must be installed after Compline of the First Sunday of Lent, and about other veils for the crosses and images, which are placed the next day before Terce:

Dominica prima Quadragesimae post Completorium suspendatur cortina inter Chorum et altare. Feria secunda ante Tertiam debent esse coopertae Crux, Coronae, Capsae, textus qui imagines deforis habent.

On the First Sunday of Lent, after Compline, let a curtain be hung up between the choir and the altar.

On Monday before Terce, the Cross, crowns, reliquaries, and the fabrics which have images [painted] on them must be covered up (Statutes ch. 1, § 3).

Here are several more references, which admittedly show some variation in detail amongst the medieval monastic uses, but which allow us to appreciate the wide extent of the use of the Lenten veil:

- Post Completorium appenditur velum inter altare et chorum quod nullus praeter Sanctuarii Custodes, atque Ministros, absque rationabili causa audet transire.

After Compline, a veil is hung between the altar and the choir, which no one besides the custodians of the sanctuary and the ministers [of the mass] should dare to cross without reasonable cause (Liber Consuetudinum S. Benigni Divionensis, Customary of St-Bénigne in Dijon).

- Dominica post completam debet Secretarius tendere cortinam inter chorum et altare et Crucifixum cooperire.

On Sunday after Compline the Sacristan must stretch out a curtain between the choir and the altar and cover the Crucifix (Liber Usuum Beccesnsium, Book of the Usages of Bec-Hellouin).

- Hac die post Completorium cruces cooperiantur, et cortina ante Presbyterium tendatur, quae ita omnibus diebus privatis per XL usque ad quartam feriam ante Pascha post Completorium remanebit. (...) In Sabbatis vero et in vigiliis SS. duodecim Lectionum ante Vesperas a conspectu Presbyterii est cortina retrahenda, et in crastino post Completorium est remittenda. Similiter retrahentur ad Missam pro praesenti defuncto, et ad exequias: Non intres in iudicium, donec septem psalmi finiantur post sepulturam. S et ad benedictionem novitii. (...) Ad missam vero privatis diebus, ut Sacerdos libere ab Abbate, si assuerit, ad Evangelium legendum benedictionem petat, Subdiaconus cornu cortinae in parte Abbatis modice retrahat, et data benedictione, ut prius erat, remittat. Diaconus vero accedat ad cortinam, ubi sublevata est, quaerens benedictionem.

On this day, after Compline, let the crosses be covered up, and a curtain be extended before the sanctuary, which must remain so on all ferial days throughout Lent until after Compline of the Wednesday before Easter. [...] On Saturdays, however, and the vigils of saints of twelve lessons, the curtain must be drawn back before Vespers that the sanctuary might be visible, and it is put back the next day after Compline. It is likewise to be drawn back on a funeral mass where the body is present, and on obsequies from Non intres in judicium until the seven penitential psalms finish after the burial, and on the blessing of a novice. [...] But on weekday masses, in order that the priest, if he wishes, can freely ask the blessing of the abbot for reading the Gospel, let the Subdeacon slightly draw back the end of the curtain at the abbot's side, and after the blessing has been given, let him put it back as it was before. But let the deacon walk up to the curtain, at the point where it is lifted up, to ask for the blessing (Liber Usuum Cisterciensium, Book of the Usages of Cîteaux, ch. 15: De Dominica prima XL). - Hac die post IX ante Sanctuarium cortina a Sacrista tendatur, et cruces in ecclesia cooperiantur. (...) In festis vero SS. XII. Lectionum, et Dominicis, die praecedente ad Vesperas a conspectu Sanctuarii cortina abstrahenda est, et in die festi post Completorium rehrahenda: similiter singulis diebus ante elevationem Domin Corporis abstrahantur, et ea facta retrahetur.

On this day after None, let a curtain be spread out before the sanctuary by the sacristan, and let the crosses in the church be covered up, [...] But on saints feasts of twelve lessons, and on Sundays, at Vespers on the preceding day the curtain is to be opened up that the sanctuary might be visible, and after Compline on the feast it is to be put back. Similarly, on each day let it be opened up before the elevation of the Body of the Lord, and closed again thereafter. (Tullense S. Apri Ordinarium, Ordinary of St-Evre-lès-Toul) - Vesperae autem diei praecedentis diem cinerum, cruces, et imagines cooperiantur, et cortina ante Presbyterium tendatur, quae ita omnibus diebus privatis usque ad quartam feriam hebdomadae palmarum dum canitur: Et velum Templi scissum est, remanebit. (...) Et omnibus etiam privatis diebus ad elevationem Dominici Corporis et Sanguinis Missae conventualis, quae cantantur in summo altari.

Now, at Vespers of the day preceding the Day of Ashes, let the crosses and images be covered up, and a curtain be stretched out before the sanctuary, which shall remain thus on all ferial days until Wednesday of the Week of Palms, when Et velum templi scissum est is sung. [...] but not on ferial days at the elevation of the Body and Blood of the Lord during conventual Mass, which is sung at the high altar. (Caeremoniae Bursfeldenses, Ceremonial of the German Benedictine Congregation of Bursfelde, ch. 31, 1474-1475)

The German Fastentuch

The Lenten veil has remained in use here and there in Sicily and in Spain, but it is especially in Germany and Austria that it has been preserved to our day. The fact that the Lenten veils (or Fastentuch in German) had there become genuine works of art by their decoration surely has something to do with their preservation, and the continuance of their use.

The Lenten veil of Paris would usually have been a rather ordinary woolen sheet (made of ‘camlet’ to employ the technical term used by Martin Sonnet in the Ceremonial of 1662), and must have remained without any special decoration for a long time, as it was in its primitive state. None of these have been conserved and we have not been able to find any ancient iconographic representations.

On the other hand, it is at the end of the 13th century that we observe, in Flanders and Germany, that Lenten veils became ornamented, first with embroidery and then with painting, becoming more and more rich and sumptuous.

Especially in southern Germany and Austria one sees that Lenten veils became very richly painted canvases representing scenes of the Passion, often true masterpieces of their time.

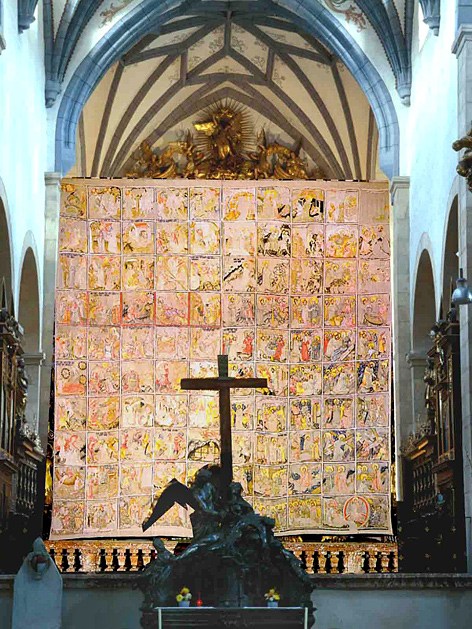

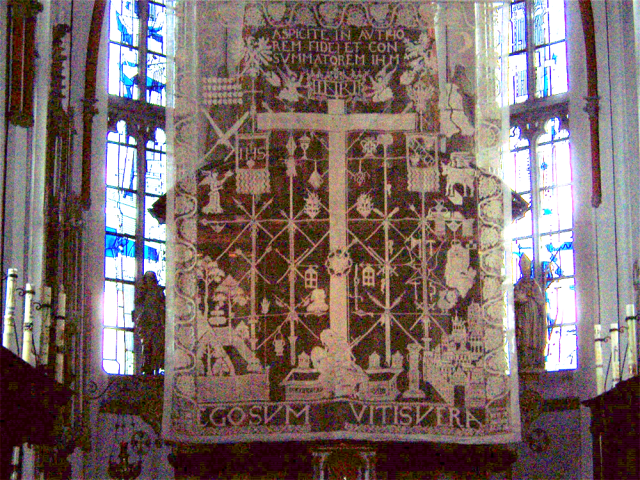

|

| Lenten Veil of the Cathedral of Fribourg (1612 |

|

| Lenten Veil of the Abbey of Millstatt in Austria (1593) |

|

| Lenten Veil of the Cathedral of Gurk in Austria (1458) |

These veils were a veritable instrument of catechesis through image, educating the people about the history of salvation.

|

| The Lenten Veil of the Cathedral of Gurk in Austria, composed of 99 tableaux from Scripture (1458) |

Martin Luther, who detested the idea of Lent and of penance, tried to make the Fastentuch disappear in all of Germany. Little by little they fell into disuse, and from the end of the 19th century the use had practically disappeared. Curiously, this ancient tradition reappeared vigorously beginning in 1974, when the charitable association Misereor had the idea of producing a Fastentuch to give concrete expression to Christians' Lenten efforts. This initiative has a certain impact all over Germany, leading to the rediscovery of this tradition, the restoration of numerous historic veils that slept in the vaults of cathedrals or museums, and their suspension in sanctuaries once more. There was so much interest that even the Lutherans were moved to put them up! Currently, it is estimated that one third of German Catholic churches as well as many hundreds of Lutheran parishes hang up a veil during Lent. From Germany the practice is expanding currently into Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland and even France.

A Tradition with Roots in Christian Antiquity

The practice of veiling images, crosses, and relics during Lent is certainly ancient in the West. Thus, we see in the life of St. Eligius, written by St. Audoin († 686), that the precious casket of the saint was covered by a veil during the entire duration of Lent. But this is not exactly the purpose of this article.

The practice of hanging a veil before the sanctuary of churches hearkens to the most ancient period.

The Old Testament, a type of the New, speaks of a veil that covered the Holy of Holies, first in the itinerant Tabernacle of the desert, then in the Temple of Jerusalem (according to St. Paul, the veil that was rent at the death of Christ was the second veil, and a first veil closed off the Holy Place. Cf. Hebrews 9:3).

The first Christian churches used the sanctuary veil as much in the West as in the East.

The ancient altar was usually covered by a ciborium or baldacchino, between whose columns veils were hung.

Besides these veils over the ciborium, the sanctuary itself was separated from the choir and the nave by a cloister called the chancel or templon, a barrier that might include columns, between which veils were hung. Twelve columns closed off the sanctuary of the basilica of the Anastasis (today the Holy Sepulchre) constructed by Constantine at the beginning of the 4th century. These columns served to support curtains, as various patristic texts tell us. The curtain of the sanctuary of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, donated by the munificence of the emperor Justinian, was made of cloth of gold and silver of an estimated cost of 2,000 minae.

This double rung of veils, the veil of the templum and the veil of the ciborium, constituted the limits of the Holy Place and the Holy of Holies in the temples of the new covenant.

The curtains were kept closed or open depending on the moments of the liturgical action. Their opening always signified the full transmission of grace and symbolized the opening of the heavens.

"When," said St John Chrysostom, "the heavenly host is upon the altar, when Jesus Christ, the royal lamb, is immolated, when you hear these words: 'Let us all pray to the Lord together', when you see that the veils and curtains of the altar are pulled back, consider that you contemplate the heavens that are opened up and the angels that come down to earth."

The West was not to be outdone: one finds in the Liber Pontificalis several references to popes (e.g. Sergius I, Gregory III, Zachary, Hadrian I) who donated veils to ornament the arcades of the ciboria and the sanctuaries of Roman churches.

Many ancient Eastern and Western liturgies contain a prayer—the prayer of the veil—that the celebrant says when, during the offertory, he leaves the choir and enters the sanctuary, going beyond the veil that closed it off.

The prayer of the veil in the Liturgy of St James, which represents the ancient use of the Church of Jerusalem, is justly renowned:

"We thank Thee, O Lord our God, that Thou hast given us boldness for the entrance of Thy holy places, which Thou hast renewed to us as a new and living way through the veil of the flesh of Thy Christ. We therefore, being counted worthy to enter into the place of the tabernacle of Thy glory, and to be within the veil, and to behold the Holy of Holies, cast ourselves down before Thy goodness: Lord, have mercy on us: since we are full of fear and trembling, when about to stand at Thy holy altar, and to offer this dread and bloodless sacrifice for our own sins and for the errors of the people: send forth, O God, Thy good grace, and sanctify our souls, and bodies, and spirits; and turn our thoughts to holiness, that with a pure conscience we may bring to Thee a peace-offering, the sacrifice of praise:

(Aloud.) By the mercy and loving-kindness of Thy only-begotten Son, with whom Thou art blessed, together with Thy all-holy, and good, and quickening Spirit, now and always:

R/. Amen."

The Assyro-Chaldean, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian Churches have kept the use of a curtain that closes off the sanctuary. In the Armenian Church, a church is considered to be in disuse if its sanctuary is bereft of a curtain. In the Byzantine church, the columns that once propped up the curtain grew coated with icons in the course of the ages and became the iconostasis: the curtain is still present, although its extension is most often limited to the breadth of the sanctuary doors.

Even if a curtain closes off the sanctuary yearlong in the East, there are nevertheless special customs during Lent. Thus, in the Armenian Church, the usual curtain is replaced during Lent by a black curtain. This black curtain always remains closed during mass and the Lenten offices, symbolizing the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise. It is not opened until Palm Sunday.

The Russians likewise change their usual brightly coloured curtain for a sombre-coloured one during the weekdays of Great Lent. All the other veils and coverings of the church are similarly changed. Brightly coloured curtains return on Holy Saturday during the Paschal Vigil, right before the singing of the Gospel of the Resurrection, while the choir sings "Rise up, O Lord, and judge the earth.”

Conclusion

Is it foreseeable that this custom will be restored in France, like it has in Germany?

Juridically, there is nothing blocking it, since the Congregation of Rites has affirmed that the use of the great veil of Lent closing off the sanctuary is indeed permissible (decr. auth. 3448, 11 May 1878).

Nevertheless, we still have something of the "visual Lent" of our forefathers since we have kept the Roman usage of veiling the crosses and statues before First Vespers of Passion Sunday (fifteen days before Easter). Even if this article is not directly about that beautiful custom, it might perhaps help us to better understand the origins of that use and to grasp its historical and symbolic depths.

---

We are grateful to the author for his permission to translate his article "Le voile de Carême – Velum quadragesimale." Translation provided by the authors of Canticum Salomonis.