|

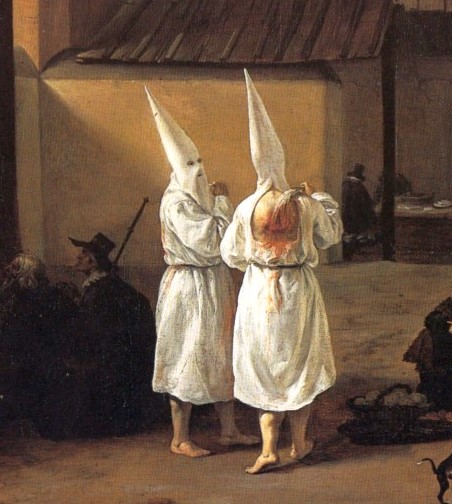

| Los Nazarenos, by Joaquin Sorolla. 1914 The Hispanic Society of New York. |

While each confraternity has their own habit and customs that may vary widely, perhaps the best-known image is that of the penitent wearing a tall conical hood, the capirote. It seems important when examining this piece of lay religious headgear to distinguish between its two component parts: the hood itself, used to preserve the penitent’s identity, called antifaz; and the stiff cone that gives it its characteristic shape, the cucurucho. The terminology is however quite irregular and the term capirote might be used for the ensemble or just the inner cone, even among different confraternities of the same city.

|

| Procession of flagellants depicting several hooded penitents. Detail from folio 74, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry by the Limbourg brothers, 1405-1409. The Metropolitan Museum, New York. |

|

| Hooded White Penitents of King Henri III, Paris, 1583-1589. Library of Congress |

|

| St John the Baptist flanked by two penitents. Early 16th century glazed terracotta lunetto at the Chiostro dello Scalzo, Florence. Picture by the author. |

The cucurucho or coroza,

on the other hand finds its origins in a paper or parchment cone hat that was

worn by public penitents. It's etymology probably derives from the latin cuculla. The coroza was later adopted by the Castilian, Aragonese and Portuguese Inquisition as standard part of the costume decreed for those condemned by the tribunals, who were automatically considered public penitents. This adoption on the part of the Inquisition at the end of the 15th century eventually made this cone shape hat deeply ingrained in the imagery of the black legend that surrounds this entire period.

|

| Procession of Disciplinants (detail), woodcut by Pieter Tanjé. Early 18th century. |

|

| Traditional mummers from the village of Ituren, Navarre, wearing the Ttuntturro. Picture by furgobidaiak.eus |

It is believed that the first confraternity two combine the two elements was the Sevillian Hermandad de San Juan de Letrán y Nuestra Señora de la Hiniesta in the 17th century and was progressively widely adopted in both Seville and the rest of Spain and even Rome. However, the arrival of the ideas of the enlightenment would lead to new legislation that forbade the “excesses” of baroque and medieval custom. Penitents were not allowed to cover their faces, and so they simply wore the antifaz with

its front part rolled up. Restrictions relaxed at the end of the 19th century, and the capirote came back with force, cradled by the romantic fashions of the time.

|

| A curious scene from Rome. Detail from The Flagellants by Pieter van Laer, 1635. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. |

|

| Holy Week in Murcia, where wearing the face covering removed has remained custom. Picture by Gregorico |

|

| In other places such as Málaga, the head covering, known colloquially as faraona is nothing but a vestigial capirote, deprived of its face covering and its cone. Picture by semanasantamalaga.info. |

|

| The author's own capirotes: original cardboard and new pvc mesh. The wet weather of northern Spain was not gentle on the cardboard, which always required haphazard repairs. |