One immediately sees here imagery of the Assumption and Immaculate Conception; that is only natural, because the Scripture passage referenced here is cited at the Introit of the Assumption, Signum magnum apparuit:

A great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and in her head a crown of twelve stars.

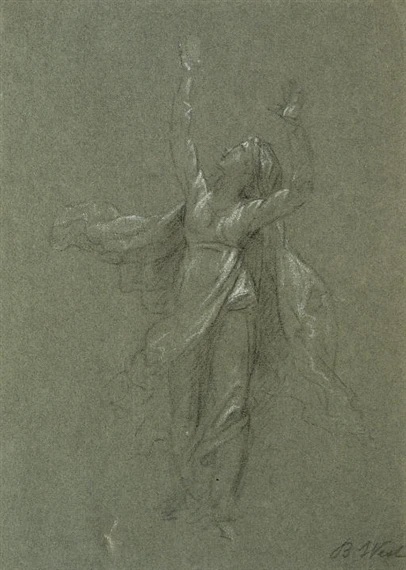

There is, however, an immediately striking oddity about this presentation: the wings. West’s study for the painting does not yet feature them:

Yet the wings are a striking and essential component in the final painting, second only to the figure herself. And to modern viewers, insistent as we are on an almost slavish historical accuracy, their addition could well look strangely out of place in a depiction of our Lady

Of course West here is only pulling from a passage further along in Apocalypse 12:

And there were given to the woman two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the desert unto her place, where she is nourished for a time and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent.(v. 14)

We know the tradition of the Italian Madonna had a strong impact on West: he modeled multiple portraits of his wife and children after Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola

Moreover, his main patron King George III, even as the head of the Anglican Church, was rather more amenable to sacred art than the more strident Protestant voices of his day. Perhaps, however, a straightforward treatment of the Virgin was a step too far. West’s early biographers indicate that he himself was not fond of the saints’ stories so well represented in Italian art. But whether his artistic avoidance of the Blessed Virgin was self-imposed, or imposed by his surroundings, he could at least sneak something of the genre into the Woman of the Apocalypse.

And Catholic art, in fact, had its own tradition of depicting the winged Woman of the Apocalypse, sometimes as a straightforward depiction of Revelation 12, but in many other cases blended more subtly into renderings of Our Lady.

The English Cloisters Apocalypse of ca. 1330 shows a particularly interesting medieval example of the former, with the Woman receiving her wings from an angel as the Dragon threatens.

Albrecht Durer engraved a winged Virgin as part of a 1497 series on the Apocalypse (The Apocalyptic Woman, detail).

Then with Peter Paul Rubens we have a thorough blending of the two images, in his Blessed Virgin Mary as Woman of the Apocalypse (ca. 1623-24) for the main altar at Freising Cathedral:

Rubens' work was commissioned by the bishop for the Cathedral, but when Church officials objected to the wings, he cited the precedents from Durer and others. Here Our Lady receives the wings from the hands of an angel, paralleling the English Cloisters Apocalypse.

The blended "Winged Virgin" tradition seems to have found something of a new vitality in the 18th century New World. The most well-known example is the sculpture Virgin of Quito, by Bernardo de Legarda (1734), which has inspired many other sculptures and paintings along the same lines in Ecuadorian devotion:

A Virgin of the Apocalypse by Mexican painter Miguel Cabrera (1760), likewise set a precedent that inspired later Mexican artists to paint similar winged Virgins in retablos and elsewhere.

Overall, the Winged Virgin is an unusual and perhaps even somewhat controversial depiction, with clear European antecedents but enjoying a revival in the 1700s that inspired some local New World traditions.

With that in mind, whatever Benjamin West’s theological limitations might have been in painting his Woman Clothed with the Sun, they strike us as something of a fortuitous fault, helping draw out subtle Scriptural connections already set forth for us by the sacred liturgy.

And perhaps, as in Ecuador and Mexico, his sacred image is worth integrating into the visual language of the American Catholic devotion.