One of the elements that one always notes within Roman churches are the beautiful large candlesticks with their candles. Of course, candles of such a tall height as is seen on such high altars are generally not feasible beyond a certain height, especially in the places that experience Mediterranean heat, since they would quickly deform -- not to mention waste a great deal of wax as they tend to drip and inconsistently burn. As such, the actual beeswax candles came to be placed inside tubes or "dummies" that approximated the look of a candle, thereby keeping them at consistent heights and using all of the beeswax in the process of burning. In Roman churches, and sometimes elsewhere, one very frequently sees these tubes decorated, often painted with flowers and other symbols.

If one looks closely as well at images of St. Peter's Basilica from prior to the Second Vatican Council, one will notice a similar approach to both altar candles as well as to those of the acolytes.

|

| See the altar candles on the Altar of the Chair |

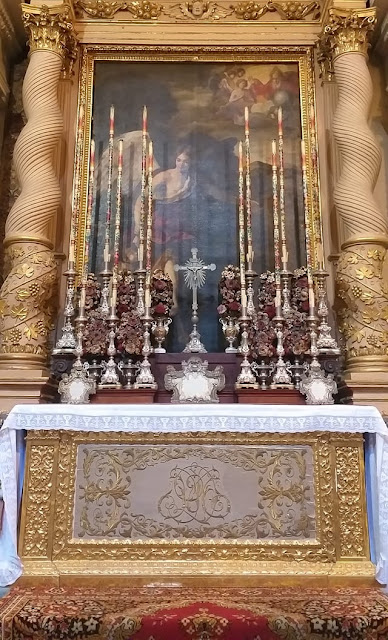

But while Rome is a place one particularly sees this, one can see it elsewhere and Italy and beyond, such as these examples from Malta and from Jerusalem.

|

| Malta |

|

| Jerusalem |

The question that arises from time to time is from whence this custom of decorating these springs? It must be said that not everything in the history of liturgical art is clearly known, and to date I have found little definitive information around this beyond a common sense explanation that candles such as these were frequently used in more solemn or festal circumstances and with those occasions comes a natural desire to add ornament.

That said, an interesting note is made by the thirteenth century author of liturgical commentary, Durandus, who makes mention in Book IV of the Rationale Divinorum Officium of how the acolytes candles "are usually decorated with lines of different colors" ("diversorum colorum lineis decorantur"); sometimes lines of gold or silver. Of course, Durandus does as medievals tended to do and offers an allegorical symbolism for this, but such allegorical explanations are notoriously more a case of assigning symbolism after the fact. In that regard, the question of origins (beyond our possible explanation of a desire to add ornamentation) still remains. However, what we do potentially gain an insight into by Durandus' comment is the fact that this sort of practice -- or at least something similar to it -- seems to have existed at least as early as the time of Durandus himself, the thirteenth century.