While the gothic revival is well enough known -- the movement by which late medieval forms and styles were re-adopted -- something one seldom seems to hear spoken of is what I am going to call the "paleochristian revival." After the centuries moved forward and the catacombs of Rome -- catacombs that in many instances had come to be forgotten and neglected due to the dangers to be found outside the city walls -- began to be re-discovered, and as the centuries progressed and the science of the field of archeology and archeological excavations began to rise, numerous items and artifacts of the paleochristian era would come to light and prominence again. Part and parcel with that was the broader, popular rediscovery of some of the earlier Christian symbols -- symbols that in great part took their cues from the classical culture from whence they sprang. This isn't to say that these symbols were entirely lost I should note for they could be found here and there on extant first millennium architectural elements, but certainly they weren't as broadly used and fell out of favour during much of the second millennium.

However, with this revival so it was that we would begin to see the Chi-Rho symbol come to greater prominence once again, as would peacocks, victory laurels/wreaths, the Greek Alpha and Omega symbols and so on.

|

| 1954-1960 |

|

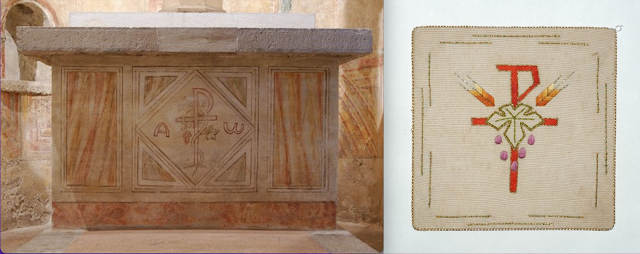

| Detail of a relief sculpted panel taken from a high altar, 1938. |

|

| Date unknown. Likely mid-twentieth century. |

|

| Date unknown. Suspect first half of the twentieth century, but possibly late nineteenth. |

The issue with taking such an approach is that it mistakes the contextual circumstances of the place and the time (namely, a time of secrecy and persecution set within the context and confines of rough-hewn, darkened burial chambers) as somehow representing a kind of ideal. It would be rather akin to taking the catacombs themselves as somehow representing the ideal form of Christian architecture.

This sort of primitivist approach to the paleochristian revival was particularly popular from the 1950's through 1980's (and still finds its advocates today, mainly from those hanging onto those decades nostalgically) and has, unfortunately left a some with a bad association in its regard. However, in point of fact, when the paleochristian revival is approached, not with primitivism and rustic minimalism, but rather by manifestations of the highest expressions and formulations of these symbols alongside the noblest materials, they can make for stunningly noble results.

Similar wreaths can be found in many parts of the old world. Here is another example taken from Ravenna from a late antique paleochristian sarcophagus.

One can readily see how easily these can be adapted into designs for altars or other architectural components.

Peacocks have been found in sculptural reliefs and mosaics since Roman times. The antique Christians adopted it as a symbol of the eternal life since it was believed by the ancient Greeks that the peacock did not decay after death. Here are some examples of its use in antique paleochristian times:

One will obviously recognize the proximity of these themes to the examples shown earlier in the article.

While all of the examples shown so far have been architectural in nature, it is probably worth mentioning the adoption of these symbols can extend beyond that.

|

| Peacocks integrated into the design of an 18th century antependium |

|

| Peacocks and the Chi Rho with Alpha and Omega symbols incorporated into a contemporary Byzantine vestment. |

The point in all of this is that, when done correctly, using sophistication in design and materials, adopting a paleochristian revival style can be extraordinarily beautiful and noble, pointing back to the antiquity of the faith on the one hand, and providing an even greater symbolic palette from which to choose on the other. We shouldn't allow less noble, more purposefully 'primitivistic' versions of this revival to push us away from what can be.