Indeed, many of us who were brought up on the new calendar have nevertheless come to prefer the older, “disunified” Lent—if you want to call it that—because we now see some definite advantage in partioning the Lenten cycle into smaller, more manageable sections. Personally speaking, Ash Wednesday has long seemed to come as sudden, almost violently stark break in the Ordinary Time after Epiphany. It's liturgical green for weeks and weeks until a Wednesday of violet, ash, and fasts. There is no liturgical transition or warning whatsoever.

Any good priest will remind us in advance to prepare for Lent's arrival, of course—but it would be nice if the liturgy had a few pointers to help him in that regard. Of course, it once did.

At Septuagesima, the Church buried the Alleluia, vested her priests in violet, and sounded the alarm that Lent was on its way. At Quinquagesima and through Shrovetide the stragglers and shirkers were given one last chance to be shriven of their sins.

Thus we were already well prepared psychologically for Ash Wednesday and the fasts. Once having entered Lent, three Sundays are allowed to go by. Then, just as our initial resolve begins to flag, we have a little bright spot—Laetare Sunday, which thankfully was preserved even in the reformed liturgy.

But instead of just sliding back into regular Lententide after Laetare week, in the older calendar we enter Passiontide—with veiled statues, more austerity, and an almost total focus on the Passion and the cross. If we have been lukewarm up until now, or have started out promisingly but then relaxed our discipline, the Church now gives us strong reminders and encouragement to start up again.

Because it is weariness, not inconsistency, that is our greatest psychological enemy during the Lenten cycle. I am reminded of hikes in mountainous terrain, where one eventually got so tired of walking downhill that an uphill stretch could come as a welcome relief. Variety brings comfort in such situations.

The coetus’s insistence on the internal unity of Lent thus seems to have addressed precisely the wrong problem. Three weeks of Septuagesima, 4 weeks of Lent proper, and 2 weeks of Passiontide, adds up to 9 weeks altogether. And still somehow it seems less wearying than 5 weeks of an invariant Lent with little change from Ash Wednesday to Holy Thursday.

One might also argue that, for consistency's sake, the 6 weeks of Lent ought to clearly mirror the 6 weeks of the Easter season. If Eastertide doesn’t get divided up into subseasons then neither should Lent.

But there are very different psychological orientations in these two seasons. The Lenten cycle is a push forward toward Calvary, while the Easter season is a lingering on the empty tomb. So it is natural for Eastertide to taper off after Easter Week. Not so Lent, where any tapering off would be completely counterliturgical.

Increasing intensity is thus inherent to the Lenten season, in a way that it can never be with Eastertide.

So wouldn’t it be best, then, to simply allow Lent its variety, as has long been the tradition of the Latin Rite?

It seems to this layman, who has kept the season both ways, that the ancient observance struck a nice balance that ought not to have been lightly abandoned in the 1960s.

|

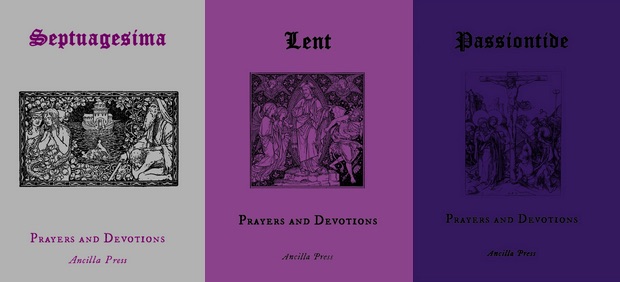

| The increasing intensity of the Lenten cycle shown through a "deepening" of penitential violet. Prayer books from Ancilla Press. |

As a matter of fact, I do not think it would even offend against the unity of Lent for additional distinctions to be drawn between these subseasons: e.g. drawing on historical vestment shades to go from a pale violet in Septuagesima to a deep violet for Passiontide.

Regardless, the subseasons of the Lenten cycle provide a liturgical variety that makes psychological sense in this gradually intensifying period of fast. I expect that more and more Catholics will find Septuagesima and Passiontide a helpful remedy against the weariness that we are susceptible to.